The 17th and 18th Centuries: Oxen and horses for were used for power. They used crude wooden plows. All sowing was done by hand and all cultivating by was done with hoe. Hay and grain were cut with a sickle. In 1793, Eli Whitney invents the cotton gin, which contributes to the success of cotton as a Southern cash crop.

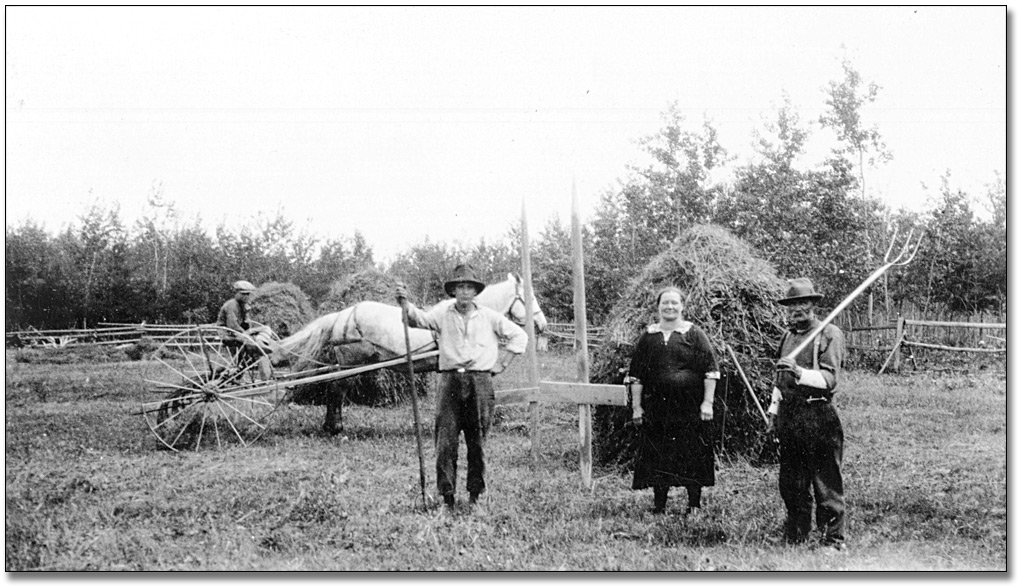

The 19th and early 20th Centuries: In the 19th century 75 percent of the population of the U.S. lived in rural America. Early 20th century agriculture was labor intensive, and it took place on a large number of small, diversified farms in rural areas where more than half of the U.S. population lived. These farms employed close to half of the U.S. workforce, along with 22 million work animals, and produced an average of five different commodities. Because farmers often did field work by hand or with horse-drawn equipment, farms were small and less efficient.

Farmers didn't know how to make their cows comfortable and because of this, they did not produce as much milk. Chickens were often left to roam around the farm they were often taken by predators or caught diseases from wild birds.

In 1940, one farmer could feed about 19 people.

By 1980, only two percent of the population of the U.S. is directly involved in agriculture.

Today, one farmer can feed 155 people.

Farmers use technologies such as motorized equipment, modified housing for animals and biotechnology, which allow for improvement in agriculture. Better technology has allowed farmers to feed more people and requires fewer people to work on farms to feed their families.

Today, most farmers use tractors and other motorized equipment to help with field work. Tractors are larger and move faster than horses, so farmers are able to work on more land and grow more food. They can run for longer periods of time and work when the farmer needs them.

Dairy cows now live in barns that have soft mattresses, sand beds or water beds for them to sleep on, nutritionists to feed them special diets, and fans and sprinklers to keep them cool when it is hot outside. Chickens aren't commonly left to roam around today. When chickens live inside, both the eggs and the meat they produce are protected from diseases, and farmers can make sure that consumers receive healthy products.

Seed technology has made it so crops can withstand harsh weather conditions, leading to increased yields.

Farmers now realize the importance of using our natural resourses wisely, because of this farmers are able to provide extra care for the land.

There are fewer farmers today because farmers are able to produce more food with the land that they have. This allows food to be more affordable in the store so fewer people go hungry.

.jpg)

Experts indicate that the world’s population will increase from approximately six billion to nine billion by 2050—all to be fed, clothed and even fueled by agricultural products. What’s more, as people rise out of poverty, higher living standards such as greater meat consumption and personal mobility will place even more demand on food crop production (wheat, rice), animal feed (corn, soybeans), fiber (wood, cotton) and fuels (sugarcane, switchgrass).

Our challenge is to increase agricultural yields while decreasing the use of fertilizer, water, fossil fuels and other negative environmental inputs. Embracing human ingenuity and innovation seems the most likely path.

Several seed development programs show promise for reducing water requirements and improving nitrogen utilization (to reduce fertilizer need) in established crops such as corn and cotton, as well as in new crops such as switchgrass and miscanthus that are desirable, nonfood feedstocks for biofuels.

Consider just one recent advance: a new nanoparticle vaccine. If successful this nanotechnology-enhanced treatment will allow cattle to receive a single vaccine for a multiple number of diseases, including bovine viral diarrhea, bovine ephemeral fever and cattle tick fever.

Fresh, locally grown produce in the middle of winter will soon become a reality for many residents around the world. In the coming years, expect ever more urban spaces to be converted to agricultural production as consumer demand for “locally grown” produce grows, and as food producers and distributors seek to lower their transportation costs and minimize their “carbon footprints.”

A small number of family diary farms are now using robots to milk cows. Ironically, rather than putting farmers out of work the technology is encouraging younger farmers to stay on the family farm because it frees them from the burden of having to be available to milk cows seven days a week. At Georgia Tech University researchers are perfecting robots to debone chickens—one of the most difficult and delicate tasks in agriculture today. As robots continue to getter better and more affordable, expect the technology to continue to move from the large corporate farms to even the smallest of family farms and, in the process, it will transform agriculture as we know it.